The Women’s Land Army & Women’s Forestry Corps by Caroline Scott

Advert for the Women’s Land Army, placed in the press in June and July 1917.

The efforts of the Women’s Land Army in the First World War have been largely forgotten, and the fact that the organisation left so few lasting marks on the landscape probably contributes to this phenomenon. The history of the Land Army is a curious clash of elements of continuity and change; ultimately it was about keeping the wheels turning, ensuring that agricultural output was maintained, but that process involved putting women into trousers and onto tractors – essentially into conventionally ‘unfeminine’ roles. It had a significant impact on those individuals involved, and arguably on accepted ideas of women’s capabilities, but made a lesser (or at least impermanent) physical impression on the structures of rural England. Bringing women onto the land required improvisation, for all involved to make the best of the resources available, and that ‘making do’ means that there’s little identifiable physical legacy today. But perhaps there are some clues and echoes out there?

By the end of 1916 it was estimated that around 350,000 male workers had left agriculture for military service, equivalent to approximately 35% of the normal workforce. A real labour shortage was starting to impact farm productivity by the spring of 1917, just as Germany’s U-boat campaign was shifting up a gear and threatening to starve Britain into surrender. It was this crisis that prompted the launch of the recruitment campaign for the Women’s Land Army (WLA) in March 1917. Notices placed in newspapers appealed for ‘10,000 Women Wanted at Once to Grow and Harvest the Victory Crops.’ By the start of May 22,603 women had come forward.

Montage showing women performing a variety of agricultural tasks at Great Bidlake, Devon, a training farm for the WLA. (The Landswoman, September 1918, No. 9, Vol. 1.)

While the recruiting propaganda offered women the possibility of making a permanent career on the land, it was also stressed that this was an emergency measure – a temporary measure – and, as such, improvisation and economy were key. Investment in physical infrastructure was limited; rather, appeals were made to landowners’ goodwill, assets were begged and borrowed, and favours were called in.

Recruits, most of whom had no previous agricultural experience, were either trained by their employer-to-be, or on designated training farms. In June 1917 a correspondent for the Whitby Gazette went along to see how Land Army trainees were getting on at Intake Farm, at Littlebeck, near Whitby. He found the women ‘clod-breaking’, and going about this monotonous duty cheerfully. Mr Ventrees, the farmer, spoke in glowing terms of how the women had adapted and learned new tasks. ‘Probably this is not to be wondered at,’ the journalist observed, ‘seeing they have been treated as members of the family and everything done to make their stay a profitable and pleasant one.’ The experience wasn’t always quite so cosy, though. In Northumbria, a training centre opened at Wideopen, on the land of the Cramlington Coal Company. The government contributed funds to furnish a house and paid towards the women’s training, while other expenses (‘cows, dummy cows, and a nanny goat for teaching the girls to milk’) were met by the Coal Company. By September 1917, 247 training centres and 140 training farms were operating.

Beatrice Bennett and fellow timber workers at Chilgrove Camp, West Sussex, 1918 ©:IWM .

As instruction varied across the country, so too would accommodation, and this was often an aspect that would prove challenging. In March 1917, the WLA promised recruits: ‘In some cases the farmworkers’ hostel may be a country mansion, in others a collection of cottages’. But vacant workers’ houses just weren’t available in any numbers, and when they were conditions were often basic. Land Girl, Dora Brazil found herself living in a cottage on a Duke’s estate in Buckinghamshire. She was in sight of the ‘country mansion’, but a long way away from its comforts and cleanliness. It ‘was terrible,’ she recalled. ‘Only the bare necessities of life, and about ten yards from some abandoned pigsties which housed a few hundred rats!’ Kathleen Gilbert took up residence amongst the pigsties too: ‘The farmer got us one of the sheds, close to the pigsties, we had that furnished out and we lived in there… the farmer’s wife had done wonders. Rugs and everything we had in there.’ She called her shed a ‘homely’ billet – though one girl’s notion of homely was perhaps different from another’s. With a lack of suitable alternative accommodation available, hostels were set up in Northumbria, at Wooler and Carham. The Wooler hostel was a bothy built for quarryman, now providing ‘cubicles for twelve girls’. Securing appropriate accommodation was a real problem in Wales too, and limited the placing of female workers there. A hostel opened in Cadoxton, near Cardiff, and a Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) depot and hostel was established in Aberystwyth. YWCA hostels also opened their doors to land workers in Bedford, Cambridge, Huntingdon, Lewes and Spalding. Forty forage workers were accommodated by the YWCA in Gloucester, the organisation offered WLA members convalescent stays in Margate, and it also provided canteens and recreation huts for the camps of flax workers.

Flax pullers, Crewkerne, Somerset, 1918.

Accommodation could be particularly primitive for timber workers. Beatrice Bennett worked at Chilgrove Camp, in West Sussex, where women were accommodated in huts – ‘like the ordinary YMCA hut’. Beatrice recorded: ‘Our beds are just off the floor on a wooden frame, a straw mattress and pillow and five blankets… the camp is miles away from anywhere, absolutely isolated. One would never imagine such a place existed.’

It would be fascinating to learn if any of these places do still exist.

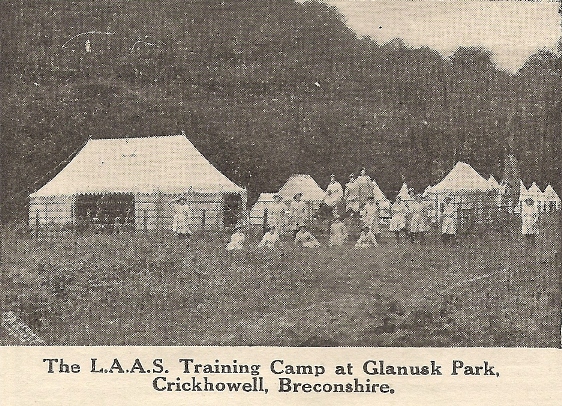

‘This camp was opened on June 22nd, 1918, for the purpose of training Land Army recruits on the surrounding farms. It is beautifully situated on the banks of the River Usk. The site was given by Lord Glanusk, who has also been most generous in supplying everything that could add to the comfort of the Camp; building wooden huts for kitchen, store-rooms and wash-houses; and having water laid on and a boiler and camp oven built. All these items have been greatly appreciated by the Staff and Trainees. There are 18 tents in all, 15 sleeping tents, a mess tent, outfit store tent, and recreation tent with piano, which is a most popular addition.’ (The Landswoman, October 1918, No. 8, Vol. 1.)

Key sources for research:

The Imperial War Museums’ collection contains a wealth of diaries, accounts, letters, photographs, official documents and recorded interviews with members of the Women’s Land Army. These can be accessed at the IWM’s London Research Room and, in the case of some sound recordings, via the museums’ website: www.iwm.org.uk

The Landswoman, the monthly magazine of the WLA, was launched in January 1918, and from the start it encouraged its readers to contribute to the text. Full of photographs, correspondence and articles written by the women workers themselves, the magazine gives a real flavour of what life in the WLA was like. Digitized copies can be viewed at www.womenslandarmy.co.uk.

Both the national and local press took a great interest in the WLA, and journalists were regularly dispatched to farms to watch the women at work. Newspapers can be searched at: www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk

Further reading:

You can find out more about the work of the Land Army in ‘Holding the Home Front: The Women’s Land Army in The First World War′. Copies are available through Pen & Sword.